Epilepsy syndromes are a high-yield topic for resident and board exams, so take the time to review this topic carefully! This chapter covers commonly tested epilepsy syndromes throughout various age groups, classic EEG findings, structural causes of epilepsy, and anti-seizure medications.

Authors: Brian Hanrahan MD, Steven Gangloff MD

Classification of Seizures

- Seizures are defined as a paroxysmal occurrence of abnormal, excessive, and/or synchronous neuronal activity of the brain. This often, but not always, causes neurological symptoms.

- Seizures are not a disorder in and of themselves but are a symptom of various neurological or systemic etiologies.

- The first step in seizure classification is to identify whether seizures are focal or generalized in onset.

Focal seizures

- Previously called partial seizures, focal onset seizures can be subclassified as focal aware or focal with impaired awareness.

- Focal aware seizure: Patient is aware of the ictal symptoms during focal seizure activity. This is often seen with frontal, parietal, and lateral or non-dominant temporal seizures.

- An example is a patient who can report a “Jacksonian march” seizure semiology. This can be more formally identified as a focal motor aware seizure.

- Focal seizure with impaired awareness: Self-awareness is not maintained with focal seizure activity, often due to involvement of the hippocampus. An example is a patient who has a temporal lobe seizure with associated semiology of staring and unresponsiveness.

- Formerly called complex partial seizures.

- Expanded classification of focal seizures adds more details regarding ictal semiology; Motor Onset (automatism, clonic, hyperkinetic, etc.), or Non-Motor Onset (behavior arrest, sensory, emotional, etc.)

- History or video recording of ictal semiology can help localize the epileptogenic focus:

- Temporal lobe seizures:

- Temporal lobe epilepsy is the most common focal epilepsy.

- Mesial temporal seizures present with an aura of unusual smell, taste, automatisms (lip-smacking, hand rubbing), or feeling of déjà vu.

- Lateralized temporal lobe epilepsy presents with auditory auras.

- Can be seen secondary to an autosomal dominant mutation in the LGI1 gene.

- Amygdala-onset seizures present with fear and autonomic symptoms (tachycardia, piloerection).

- Parietal lobe seizures: Can present with hemibody paresthesias or other primarily sensory manifestations.

- Frontal lobe seizures: Diverse, but often involve hyperkinetic or bilateral atypical movements, such as clapping and leg bicycling. These may be brief and sudden, arise from sleep, and have minimal post-ictal confusion.

- Seizures of the supplementary motor area (SMA) of the frontal lobe present with fencer posturing:

- Extension of the contralateral arm, flexion of ipsilateral arm. Head and eyes will face the contralateral side.

- Seizures of the supplementary motor area (SMA) of the frontal lobe present with fencer posturing:

- Occipital lobe seizures: Can present with visual phenomena.

- Temporal lobe seizures:

What you need to know

Be able to identify the focal seizure onset by reported seizure semiology.

- Focal seizure to bilateral tonic-clonic seizure: Presents with a focal onset of symptoms with progression to involve the whole cortex and bilateral tonic-clonic activity.

- Used to be called partial seizure with secondary generalization.

Generalized seizures

- Presets with an acute onset of ictal activity involving the whole cortex or bilateral cortex simultaneously.

- Examples of generalized seizures include absence, myoclonic, tonic-clonic, and infantile spasms.

- Usually, after a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, the EEG will show a generalized low-amplitude record with irregular slowing known as electrodecrement.

First Time Seizure

- When a patient presents with a first-time seizure, a thorough workup to evaluate for any provoking factors should be completed.

- This includes an EEG and CT or MRI.

- If no underlying etiology is found then most often patients do not require starting anti-seizure medications (ASMs) unless the patient is deemed a high risk for recurrent episodes.

- Risk factors for recurrence include focal neurologic exam, nocturnal seizure, epileptiform discharges on EEG, and history of prior brain insult or an abnormal MRI/CT scan.

- The risk for recurrence is greatest in the first 2 years from a first-time unprovoked seizure.

- Immediate ASM usage after a first-time unprovoked seizure will reduce the risk of seizure recurrence in the first 2 years, but will not improve long-term prognosis or quality of life.

The Diagnosis of Epilepsy

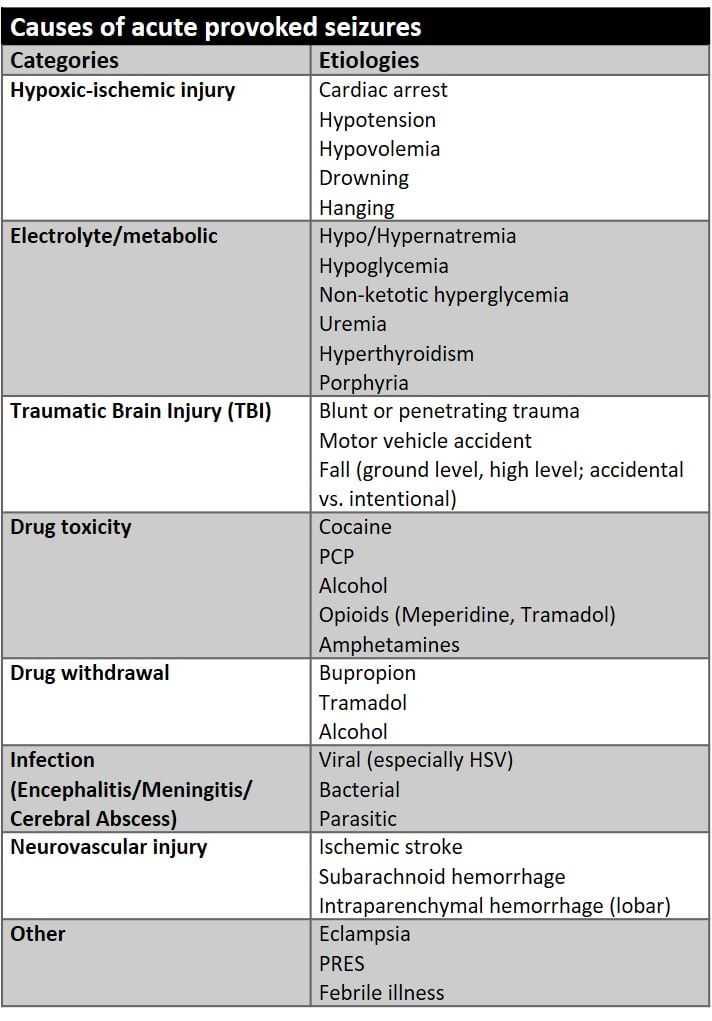

- Just because someone has seizures doesn’t mean they have epilepsy. For example, a patient with provoked seizures due to alcohol withdrawal does not have epilepsy. Seizures that are the result of an acute direct or indirect brain insult are termed “provoked” seizures.

- Most provoked seizures that occur secondary to an indirect brain insult (drug toxicity, electrolyte abnormality, etc.) present with generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Note

Patients with acute provoked seizures related to an indirect, reversible brain insult often do not require long-term anti-seizure medications (ASMs)! However, those with a structural injury to the brain who continue to have seizures after the acute phase of their insult require long-term ASMs.

- The International League Against Epilepsy in 2014 decided that a patient can be diagnosed with epilepsy if they meet one of three following criteria:

- Had two unprovoked seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart.

- Had one unprovoked seizure, and the probability of further seizures is deemed by the practitioner to be higher than 60%.

- Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome.

- After a patient is diagnosed with epilepsy, diagnostic studies, and clinical history can help identify if they have focal or generalized epilepsy.

- Focal epilepsy can also be called symptomatic epilepsy and generalized epilepsy can also be called idiopathic or genetic epilepsy.

- Some epilepsy syndromes like Lennox-Gastaut and Dravet syndrome can present with both focal and generalized seizures.

- There are six etiologic categories that lead to epilepsy:

- Genetic: This typically represents generalized epilepsy syndromes (absence epilepsy, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME), Doose syndrome, etc.).

- Structural: Mesial temporal sclerosis, focal cortical dysplasia, heterotopia, and acquired brain injuries (stroke, trauma).

- Metabolic: Mitochondrial disorders, glucose transporter (GLUT-1) deficiency, and peroxisomal disorders.

- Presents predominantly in the neonatal or infancy period.

- Immune: Rasmussen encephalitis, NMDA receptor encephalitis, etc.

- Infectious: Viral encephalitis/meningitis, toxoplasma gondii, neurocysticercosis, cerebral malaria, etc.

- Unknown: Formerly known as cryptogenic, this title is reserved for those with no clear etiology.

Neonatal Epilepsy Syndromes

- An epilepsy syndrome represents a combination of clinical features (EEG pattern, seizure type(s), comorbidities, etc.) that usually occur together. They can be specific to a particular genetic etiology or can be secondary to a range of causes. We will discuss various high-yield epilepsy syndromes broken down by age.

Benign neonatal seizures (Non-familial)

- Presents usually around the 4th-6th day of life with seizures, typically unifocal clonic, in otherwise healthy infants.

- Formerly called “fifth-day fits” or “benign idiopathic neonatal convulsions, BINC.”

- Seizures are frequently self-limiting and resolve without intervention after a couple of days.

- KCNQ2 sporadic and de novo mutations have been reported. The association is less pronounced than in BFNE but suggests some overlap between these disorders.

Self-limited familial neonatal epilepsy (SeLNE)

- Formerly called benign familial neonatal epilepsy (BFNE), benign familial neonatal seizures (BFNS), or benign familial neonatal convulsions (BFNC).

- An autosomal dominant disorder that presents usually around the 2nd-3rd day of life with various seizure types in otherwise healthy infants.

- Remission by 6 months is typical.

- There is a strong association with potassium channel defects (KCNQ2 or KCNQ3 gene mutations)

Reminder

KCNQ2 gene mutations can present with a spectrum of epileptic phenotypes with a range of disease severity.

Myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (MEI)

- Presents between 6 months to 2 years of life with focal myoclonic seizures, focal motor seizures, and tonic spasms.

- EEG shows spike-wave and polyspike and waves with myoclonic jerks. Interictal EEG can be normal but can have a burst suppression pattern, particularly during sleep.

- May have “reflex seizures” triggered by startling noise or tactile stimulation.

- The reflex variant carries a good prognosis.

- Valproic acid is valuable in the management of the myoclonic activity.

Note:

The SCN1A gene codes for a sodium channel subunit that, when mutated, can lead to a spectrum of epileptic syndromes, including Dravet syndrome and GEFS+. If sodium channel blockers (lamotrigine, phenytoin, carbamazepine, etc.) are given to someone with an SCN1A mutation-related epilepsy it will actually make their seizures worse!

Reminder:

Acute insult (hemorrhagic/ischemic stroke, hypoxic-ischemic injury, etc.) is the most common cause of neonatal seizures.

Log in to View the Remaining 60-90% of Page Content!

New here? Get started!

(Or, click here to learn about our institution/group pricing)1 Month Plan

Full Access Subscription

$142.49

$

94

99

1 Month -

Access to full question bank

-

Access to all flashcards

-

Access to all chapters & site content

3 Month Plan

Full Access Subscription

$224.98

$

144

97

3 Months -

Access to full question bank

-

Access to all flashcards

-

Access to all chapters & site content

1 Year Plan

Full Access Subscription

$538.47

$

338

98

1 Year -

Access to full question bank

-

Access to all flashcards

-

Access to all chapters & site content

Popular

Loading table of contents...

Loading table of contents...